Oregon girl sent to Mexico falls through the cracks

Oregon officials place foster child Adrianna Romero Cram, 4, with relatives in Mexico, where child welfare agencies in two countries fail to protect her

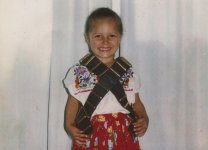

Adrianna Romero Cram smiles in a photograph taken in Mexico before she was murdered.

Sunday, March 15, 2009

By Susan Goldsmith and Michelle Cole

The Oregonian

The dark-haired American girl was suffering. The teachers at her preschool in the Mexican village had seen the bruises.

The Series

Adrianna's Story & Video

But Adrianna Romero Cram, just 4 years old, a U.S. citizen shipped from Oregon foster care to relatives she'd never met in Mexico, had little to say about what was happening to her.

"Who hit you, Adriannita?" asked teacher Judith Caizero Aguilar. "Who hit you? I won't tell anybody."

The little girl had only one answer for her teacher: "I fell."

But she hadn't fallen. Adrianna was being abused.

Adrianna's torment continued for months because governments in two countries failed a little girl they were supposed to protect.

The state of Oregon sent Adrianna to Mexico and had legal responsibility for her well-being. But an investigation by The Oregonian shows that the state's monitoring of her welfare was limited to occasional phone calls -- mostly to her abusers -- and unquestioning dependence on welfare workers in Mexico. Mexican authorities didn't make adequate checks on Adrianna's care and blatantly ignored repeated warnings that she was being abused.

Today little has been done on either side of the border to ensure the safety of American children sent from foster care to live with relatives in Mexico.

Nationally, nobody can say exactly how many U.S.-born children have been sent from state foster care to live in other countries. There's no reliable system to keep track of what happens to these children. What is clear is that the majority go to Mexico.

Adrianna made that journey 10 months before the spring day when her teacher asked the little girl who hit her.

That frightened child was very different from the one who'd arrived in Omealca, a town of 3,600 surrounded by verdant hills and sugar cane fields in the southern Mexico state of Veracruz. The school's director recalled her as an "adorable, happy child" her first few months.

But by winter, teachers noticed that the bubbly girl who loved wearing hats was quiet, withdrawn and not dressed properly for the cold mornings. She told them she was hungry.

As summer approached, Adrianna's anguish was in full view: bruises on her legs and back, a chunk of hair pulled from her head, burns on her palms.

The teacher, Caizero Aguilar, tried to comfort the little girl.

"I told her, 'The angels protect you. In the night, the angels will come and take you on a beautiful trip,'" Caizero Aguilar said, hoping that the girl would feel safe.

"'Don't have fear, Adrianna. The angels will protect you.'"

Reporters for The Oregonian have filed records requests and interviewed state officials about the case since August. On Tuesday, as this series was being prepared for publication, Oregon's Department of Human Services announced a moratorium on sending foster children out of the country. State officials say they want to develop international agreements before more children are sent abroad.

Oregon has sent 13 children to Mexico for adoption since 1999; state officials expect the number to grow. Five children were in the pipeline for Mexico when the moratorium took effect.

For the children who've already been sent to Mexico and for those who may follow, it's important to understand what happened to Adrianna.

Why did she have to turn to angels?

Rough start

Adrianna was born in the summer of 2000 at Hillsboro's Tuality Community Hospital to a 17-year-old mother who refused to touch her.

"I believed everything I touched I made garbage," said Adrianna's mother, Tausha Cram.

State records repeatedly refer to Cram's "turbulent" childhood. Turbulent may be too gentle a word.

Born in Washington state, she moved frequently. She was sexually abused as a child and addicted to meth by 13. She dropped out of school and became pregnant with Adrianna when she was 16.

Adrianna's father, Basilides Romero Marin, was from Mexico and also a teenager. He was violent, records show, and the marriage lasted less than a year.

Teachers' Notes

Teachers at Adrianna Romero Cram's preschool documented her abuse in hopes of getting help for the little girl. Their notes from 2005, along with photos they took of Adrianna's injuries, became part of the criminal investigation following her murder. Here are excerpts, translated from the original Spanish and edited for clarity:

May 19:

Teacher: What happened to your hands and your ear? Adrianna: Elizabeth Romero Marin, Adrianna's aunt, "put my hands on the stovetop and had to put toothpaste on it." She pulled my ear because she said "you dirtied your house dress" and "I had to bleed you for that." Teacher: What about your head? Adrianna: "I climbed on top of the hammock and had to hit my head." Teacher asks about eating at home.

Adrianna: "I like to eat tortilla."

Romero Marin "says eat good and with your mouth closed because if your (uncle) sees you he will see how you eat like a little pig."

"She says that I don't have to eat, but I wanted to eat, but she says you will eat, but you will not throw up."

June 2:

Romero Marin approached a teacher and commented that she feels tense and pressured, feeling a distancing from Adrianna, noticing that it is becoming very difficult even to comb her hair because of the lack of affection she feels. She said her daughter noticed it and asked why she didn't like Adrianna anymore. She also mentioned that she stopped sending Adrianna to the psychologist.

June 6:

Adrianna showed up with a big bruise on her mouth, specifically on the corner of her mouth and inside, too. When asked, she said she "bit her lip."

June 8:

Today Adrianna was checked more thoroughly, and new bruises and scrapes were discovered (more recent than the ones we already knew about). On her stomach on her right side, there's a bruise. She says that "it just appeared." When asked how, she answered, "just because" and "the mosquitoes bit me."

She also has a couple of scrapes on her chest that seem deep. When asked what happened, she says that she cut herself with a knife when Romero Marin stepped out for a minute. Later, she volunteers, "the mosquitoes bit me and (Romero Marin) had to punish me." I asked, because the mosquitoes bit you, she punished you? She said, "yes."

I also asked her about eating breakfast before school and she answered, "Yesterday she didn't feed me." I asked her, how about today? "No, today neither."

June 9:

Today I checked her out again and there's the same scars from the day before, but today she says Romero Marin "hit me with her shoe." I asked her what part of the shoe and she said "the heel." She also said Romero Marin hits her with her belt, with her hand, with a flip-flop and with a yellow belt. She says Hector de Jesus Luna, her uncle, hits her with a dirty undershirt.

When asked about a bruise on her right cheek, Adrianna says Romero Marin hit her for accepting the soup that a neighbor lady offered her.

Just before and just after Adrianna's first birthday, records show anonymous calls to an Oregon child abuse hot line. The baby wasn't getting the thyroid medication she needed, callers reported, and her mother was using drugs.

Cram denies the accusations, but soon after the third call, state child welfare authorities stepped in and placed Adrianna in foster care.

Caseworkers described 1-year-old Adrianna as an "adorable" toddler. Doctors and social workers chronicled the little girl's life: At 15 months, Adrianna could say: "hi," "bye" and "ho ho" for Santa. She enjoyed wearing pretty clothes.

But they also noted concerns: At 17 months, Adrianna's motor and language skills were those of a younger child. At 2 years, 7 months, Adrianna would have "bad days," when she was too calm, didn't play or eat. Other times she wouldn't tolerate being touched or changed. One doctor observed: "A better plan needs to be in place for her."

Under federal and state guidelines, children are in state custody for the shortest time possible. The idea is to assure a child a permanent home within 36 months, whether it's with the parent or someone else, preferably a relative.

Adrianna was in three foster homes that first year. She was moved from one home because a foster parent abused prescription drugs.

Meanwhile, Cram was in and out of drug treatment. Sometimes her supervised visits with Adrianna at the child welfare office were tearful, loving reunions.

Sometimes she didn't show up.

On Jan. 20, 2004, Cram was serving time in the Washington County jail when she was notified that the court would terminate her parental rights.

Adrianna's father lived in Washington state. Records show child welfare caseworkers there said he wasn't fit to parent the girl because he was in the country illegally, had a theft charge and had lied to police regarding his identity. The Oregonian was not able to reach him or confirm his immigration status.

Adrianna was nearly 4 years old and in need of a permanent family. After Oregon officials ruled out Cram's relatives, Washington County Judge Kirsten Thompson ordered the girl's father to come up with a list of his relatives who might be willing to adopt her. He suggested his father or a sister in Omealca, Mexico.

Mexican social workers recommended a different sister, Elizabeth Romero Marin. She was 24, married and had two children close to Adrianna's age. In a two-page home study, Mexican officials reported that Romero Marin and her husband, Hector de Jesus Luna, owned their three-room home, which was clean and had an indoor toilet.

Thompson signed off on a plan allowing James Perillo, Adrianna's bilingual caseworker, to take the little girl to Mexico for an eventual adoption. Even though Adrianna was going to Mexico, Oregon would remain legally responsible for her until the adoption was final, which can take a year or more.

Oregon had already sent more than a dozen kids to other countries but still had no policy for handling international adoptions. Perillo was on his own.

He said he proceeded the same way he would have had he taken Adrianna to relatives in Minnesota. Adrianna's pediatrician outlined her medical needs. Doctors in Mexico said they could care for her. Perillo said he called Romero Marin and talked to her about her home and family. "I wanted to hear that they were dedicated."

Stability at first

Omealca doesn't show up in most guidebooks to Mexico. It's three hours inland from the coastal town of Veracruz, where cruise ships dock before they head east to Cancun and Cozumel.

Despite its lush mountain setting, Omealca's poverty is striking. One-room concrete houses line crooked, dirt streets where dogs roam unattended. Garbage is strewn on the roadsides. Residents say there's little work outside the sugar cane fields, and most of the men have ditched the town for the United States to find jobs.

Others turn to drug trafficking, evidenced by the federal police who now patrol the town square with assault rifles.

Adrianna arrived in Omealca in the summer of 2004. At first, it looked as if she'd finally found some stability.

She loved playing with her cousins. And she began government-funded preschool in a one-story complex with an outdoor play area a few blocks from her home.

But within months, teachers saw Adrianna come to school without proper clothes for the weather. She was often cold and hungry. School director Albina Cruz Gutierrez spoke with Romero Marin, and the girl's care improved temporarily.

Boy at center of 2007 adoption dispute thrives

Gabriel Brandt, the little boy at the center of a 2007 adoption dispute that captured international attention, is now learning to count to 10 and living a quieter life near the Oregon coast.

Child welfare officials set off an emotional tug of war when they decided to send the toddler, a U.S. citizen, to Mexico to be raised by his grandmother.

Angela and Steve Brandt of Toledo, who had been Gabriel's foster parents since he was 4 months old, were devastated by the decision and worried about the boy's safety. They sued to keep him.

The Brandts prevailed, but not before drawing Gov. Ted Kulongoski, then-U.S. Sen. Gordon Smith and others into debate over sending children from Oregon foster care to other countries to be adopted by relatives.

Two state adoption panels recommended sending Gabriel to live with his paternal grandmother, Cecilia Martinez, in San Jose Miahuatlan, a small farming community outside Mexico City.

Mediated talks between the Brandts and Martinez led to an agreement that allowed the Brandts to adopt Gabriel but ensures contact with family in Mexico.

Last May, the Brandts took Gabriel to Mexico. Angela Brandt said Gabriel's grandmother and family were gracious hosts but that conditions of the home and village were "so much worse" than she expected.

The families talk occasionally by phone, but there are no plans for another visit to Mexico, Angela Brandt said. "We're not wealthy."

Born Gabriel Allred, but now named Gabriel Justice Brandt, the boy enjoys singing the "ABC song" and is quite possibly "the most finicky eater on the planet," his mother says.

He lives with four older brothers and two dogs. He adores "Teaspoon," a puppy the family got last Christmas, and "Bonnie," a golden retriever who "tolerates him rolling around with her," Angela Brandt said. "He told me he wants '1, 2, 3, 4, 5 dogs!'"

— Michelle Cole

In December, five months after Adrianna's arrival, her grandfather, Joel Romero Palacios, went to Desarrollo Integral de la Familia, the Mexican child welfare agency, and told them Adrianna was the victim of family violence.

Information about that report made it back to Oregon authorities via the Mexican Consulate, including an assessment by a welfare agency psychologist that said Adrianna had "defecated in her underwear," so Romero Marin "bathed her outside with cold water."

Perillo said he made phone calls to Mexico, talking with the psychologist, the social worker and Romero Marin. His notes do not describe what they talked about even though department guidelines require detailed documentation.

Perillo never talked to Adrianna's teachers, saying he assumed they would report any problems to the Mexican social workers.

He had to trust his counterparts in Mexico who told him Adrianna was all right, Perillo said. "What could I do? I had no choice."

Still, Perillo admitted that he wasn't getting the regular written updates on Adrianna that he'd requested. After the December report, he received no other written report until April. His monitoring largely meant monthly phone calls to Romero Marin.

Perillo also occasionally spoke with Adrianna.

On May 16, 2005, he wrote in the case file: "I talked to Adriana (sic) who seems fine. I told her I was going to Mexico next week. Adriana (sic) asked me if I was going to visit her. I told her I was going to another place in Mexico. She said, 'OK.'"

It would be the last contact he'd have with the girl.

Cries for help

Mexican welfare workers' spotty communiques about Adrianna's new life in Mexico made no mention of what Adrianna's family members, teachers and even some neighbors knew: The 4-year-old American girl was being beaten regularly.

By May, the principal and several teachers at Adrianna's school began a desperate effort to get the Mexican child welfare agency to pay attention. They took daily pictures of Adrianna's bruises and wounds and went to the agency's offices pleading for help.

None of the teachers' information was ever conveyed to Oregon officials, who still had responsibility for Adrianna.

On May 19, Albina Cruz Gutierrez, the school's principal, wrote a letter to the head of the welfare office in Omealca asking for urgent help because Adrianna was showing up at school with bruises on her face, hands, legs and back.

Officials responded with a letter that said a social worker visited the school May 23, assessed all the children and found them to be in "perfect health." Adrianna, the letter noted, was absent from preschool that day.

Cruz Gutierrez then went to the local office and urged them to investigate. "They said, 'Don't worry,'" she recalled. "'We'll investigate.'"

But no investigation began.

Frustrated, the principal dispatched two teachers to Xalapa, the state's capital, to see whether child welfare officials there might help.

"We told them that, if they didn't do their jobs, we were going to the prosecutors and going to press charges," Cruz Gutierrez said.

The principal also sent two teachers to Adrianna's home to check on her after she'd missed several days of school. The teachers did not see her, so Cruz Gutierrez went to speak with Romero Marin.

"She told me Adrianna didn't behave," the principal recalled. "I told her I didn't want her to hurt Adrianna and she should treat her like her other children."

Adrianna returned to school. But each day, teachers say, they found new cuts, bruises and burns, which they fastidiously documented in photos and written reports.

On June 6, the school's records show Adrianna came to preschool with a large bruise on her face, near her mouth. She told teachers she'd bitten her lip.

Two days later, Cruz Gutierrez and teachers checked Adrianna again and found a new bruise on her stomach. Adrianna said it was a mosquito bite.

Music teacher Jazmin Juarez Benitez spent much of her time off looking for help for Adrianna.

After fruitless visits to the child welfare offices around the state, she went to a Mexican human rights group, where she was told she needed to go through child welfare authorities. Frustrated, and convinced that the little girl was in danger, Juarez Benitez also went to the state attorney general's office in Cordoba, a bustling city a half-hour's drive from Omealca.

Prosecutors told her to gather all the evidence of abuse and get Adrianna's birth certificate and other paperwork in order.

When she reported back to Cruz Gutierrez, the principal called the preschool staff together to discuss how to proceed.

"I wanted to see if we had enough evidence," she recalled. "We did not have enough. We were gathering it."

Some of the teachers discussed kidnapping Adrianna for her own safety. Some were fearful.

"Omealca is known as a very violent and aggressive place," Juarez Benitez said. They were supposed to work through the welfare agency, but the officials charged with caring for the child repeatedly ignored their pleas.

Juarez Benitez said she was tormented.

"I felt Adrianna needed help urgently," she said in a phone interview a few weeks ago. "I felt very handcuffed."

On June 10, a Friday, teacher Caizero Aguilar questioned Adrianna about her abuse. She got no answers.

Frustrated by the apathy of welfare officials and the child's obvious pain, the teacher reached for her faith. The angels, she promised Adrianna, would protect her.

On Monday, Adrianna didn't show up for preschool. Hector de Jesus Luna, Romero Marin's husband, told the principal, Cruz Gutierrez, that the girl was sick and he was taking her to the doctor.

Two hours later, the principal called the doctor to check on Adrianna.

The little American girl was dead.

Susan Goldsmith: 503-294-5131; susangoldsmith@news.oregonian.com

Michelle Cole: 503-294-5143; michellecole@news.oregonian.com

Adrianna's Story - oregonlive.com

Oregon officials place foster child Adrianna Romero Cram, 4, with relatives in Mexico, where child welfare agencies in two countries fail to protect her

Adrianna Romero Cram smiles in a photograph taken in Mexico before she was murdered.

Sunday, March 15, 2009

By Susan Goldsmith and Michelle Cole

The Oregonian

The dark-haired American girl was suffering. The teachers at her preschool in the Mexican village had seen the bruises.

The Series

Adrianna's Story & Video

But Adrianna Romero Cram, just 4 years old, a U.S. citizen shipped from Oregon foster care to relatives she'd never met in Mexico, had little to say about what was happening to her.

"Who hit you, Adriannita?" asked teacher Judith Caizero Aguilar. "Who hit you? I won't tell anybody."

The little girl had only one answer for her teacher: "I fell."

But she hadn't fallen. Adrianna was being abused.

Adrianna's torment continued for months because governments in two countries failed a little girl they were supposed to protect.

The state of Oregon sent Adrianna to Mexico and had legal responsibility for her well-being. But an investigation by The Oregonian shows that the state's monitoring of her welfare was limited to occasional phone calls -- mostly to her abusers -- and unquestioning dependence on welfare workers in Mexico. Mexican authorities didn't make adequate checks on Adrianna's care and blatantly ignored repeated warnings that she was being abused.

Today little has been done on either side of the border to ensure the safety of American children sent from foster care to live with relatives in Mexico.

Nationally, nobody can say exactly how many U.S.-born children have been sent from state foster care to live in other countries. There's no reliable system to keep track of what happens to these children. What is clear is that the majority go to Mexico.

Adrianna made that journey 10 months before the spring day when her teacher asked the little girl who hit her.

That frightened child was very different from the one who'd arrived in Omealca, a town of 3,600 surrounded by verdant hills and sugar cane fields in the southern Mexico state of Veracruz. The school's director recalled her as an "adorable, happy child" her first few months.

But by winter, teachers noticed that the bubbly girl who loved wearing hats was quiet, withdrawn and not dressed properly for the cold mornings. She told them she was hungry.

As summer approached, Adrianna's anguish was in full view: bruises on her legs and back, a chunk of hair pulled from her head, burns on her palms.

The teacher, Caizero Aguilar, tried to comfort the little girl.

"I told her, 'The angels protect you. In the night, the angels will come and take you on a beautiful trip,'" Caizero Aguilar said, hoping that the girl would feel safe.

"'Don't have fear, Adrianna. The angels will protect you.'"

Reporters for The Oregonian have filed records requests and interviewed state officials about the case since August. On Tuesday, as this series was being prepared for publication, Oregon's Department of Human Services announced a moratorium on sending foster children out of the country. State officials say they want to develop international agreements before more children are sent abroad.

Oregon has sent 13 children to Mexico for adoption since 1999; state officials expect the number to grow. Five children were in the pipeline for Mexico when the moratorium took effect.

For the children who've already been sent to Mexico and for those who may follow, it's important to understand what happened to Adrianna.

Why did she have to turn to angels?

Rough start

Adrianna was born in the summer of 2000 at Hillsboro's Tuality Community Hospital to a 17-year-old mother who refused to touch her.

"I believed everything I touched I made garbage," said Adrianna's mother, Tausha Cram.

State records repeatedly refer to Cram's "turbulent" childhood. Turbulent may be too gentle a word.

Born in Washington state, she moved frequently. She was sexually abused as a child and addicted to meth by 13. She dropped out of school and became pregnant with Adrianna when she was 16.

Adrianna's father, Basilides Romero Marin, was from Mexico and also a teenager. He was violent, records show, and the marriage lasted less than a year.

Teachers' Notes

Teachers at Adrianna Romero Cram's preschool documented her abuse in hopes of getting help for the little girl. Their notes from 2005, along with photos they took of Adrianna's injuries, became part of the criminal investigation following her murder. Here are excerpts, translated from the original Spanish and edited for clarity:

May 19:

Teacher: What happened to your hands and your ear? Adrianna: Elizabeth Romero Marin, Adrianna's aunt, "put my hands on the stovetop and had to put toothpaste on it." She pulled my ear because she said "you dirtied your house dress" and "I had to bleed you for that." Teacher: What about your head? Adrianna: "I climbed on top of the hammock and had to hit my head." Teacher asks about eating at home.

Adrianna: "I like to eat tortilla."

Romero Marin "says eat good and with your mouth closed because if your (uncle) sees you he will see how you eat like a little pig."

"She says that I don't have to eat, but I wanted to eat, but she says you will eat, but you will not throw up."

June 2:

Romero Marin approached a teacher and commented that she feels tense and pressured, feeling a distancing from Adrianna, noticing that it is becoming very difficult even to comb her hair because of the lack of affection she feels. She said her daughter noticed it and asked why she didn't like Adrianna anymore. She also mentioned that she stopped sending Adrianna to the psychologist.

June 6:

Adrianna showed up with a big bruise on her mouth, specifically on the corner of her mouth and inside, too. When asked, she said she "bit her lip."

June 8:

Today Adrianna was checked more thoroughly, and new bruises and scrapes were discovered (more recent than the ones we already knew about). On her stomach on her right side, there's a bruise. She says that "it just appeared." When asked how, she answered, "just because" and "the mosquitoes bit me."

She also has a couple of scrapes on her chest that seem deep. When asked what happened, she says that she cut herself with a knife when Romero Marin stepped out for a minute. Later, she volunteers, "the mosquitoes bit me and (Romero Marin) had to punish me." I asked, because the mosquitoes bit you, she punished you? She said, "yes."

I also asked her about eating breakfast before school and she answered, "Yesterday she didn't feed me." I asked her, how about today? "No, today neither."

June 9:

Today I checked her out again and there's the same scars from the day before, but today she says Romero Marin "hit me with her shoe." I asked her what part of the shoe and she said "the heel." She also said Romero Marin hits her with her belt, with her hand, with a flip-flop and with a yellow belt. She says Hector de Jesus Luna, her uncle, hits her with a dirty undershirt.

When asked about a bruise on her right cheek, Adrianna says Romero Marin hit her for accepting the soup that a neighbor lady offered her.

Just before and just after Adrianna's first birthday, records show anonymous calls to an Oregon child abuse hot line. The baby wasn't getting the thyroid medication she needed, callers reported, and her mother was using drugs.

Cram denies the accusations, but soon after the third call, state child welfare authorities stepped in and placed Adrianna in foster care.

Caseworkers described 1-year-old Adrianna as an "adorable" toddler. Doctors and social workers chronicled the little girl's life: At 15 months, Adrianna could say: "hi," "bye" and "ho ho" for Santa. She enjoyed wearing pretty clothes.

But they also noted concerns: At 17 months, Adrianna's motor and language skills were those of a younger child. At 2 years, 7 months, Adrianna would have "bad days," when she was too calm, didn't play or eat. Other times she wouldn't tolerate being touched or changed. One doctor observed: "A better plan needs to be in place for her."

Under federal and state guidelines, children are in state custody for the shortest time possible. The idea is to assure a child a permanent home within 36 months, whether it's with the parent or someone else, preferably a relative.

Adrianna was in three foster homes that first year. She was moved from one home because a foster parent abused prescription drugs.

Meanwhile, Cram was in and out of drug treatment. Sometimes her supervised visits with Adrianna at the child welfare office were tearful, loving reunions.

Sometimes she didn't show up.

On Jan. 20, 2004, Cram was serving time in the Washington County jail when she was notified that the court would terminate her parental rights.

Adrianna's father lived in Washington state. Records show child welfare caseworkers there said he wasn't fit to parent the girl because he was in the country illegally, had a theft charge and had lied to police regarding his identity. The Oregonian was not able to reach him or confirm his immigration status.

Adrianna was nearly 4 years old and in need of a permanent family. After Oregon officials ruled out Cram's relatives, Washington County Judge Kirsten Thompson ordered the girl's father to come up with a list of his relatives who might be willing to adopt her. He suggested his father or a sister in Omealca, Mexico.

Mexican social workers recommended a different sister, Elizabeth Romero Marin. She was 24, married and had two children close to Adrianna's age. In a two-page home study, Mexican officials reported that Romero Marin and her husband, Hector de Jesus Luna, owned their three-room home, which was clean and had an indoor toilet.

Thompson signed off on a plan allowing James Perillo, Adrianna's bilingual caseworker, to take the little girl to Mexico for an eventual adoption. Even though Adrianna was going to Mexico, Oregon would remain legally responsible for her until the adoption was final, which can take a year or more.

Oregon had already sent more than a dozen kids to other countries but still had no policy for handling international adoptions. Perillo was on his own.

He said he proceeded the same way he would have had he taken Adrianna to relatives in Minnesota. Adrianna's pediatrician outlined her medical needs. Doctors in Mexico said they could care for her. Perillo said he called Romero Marin and talked to her about her home and family. "I wanted to hear that they were dedicated."

Stability at first

Omealca doesn't show up in most guidebooks to Mexico. It's three hours inland from the coastal town of Veracruz, where cruise ships dock before they head east to Cancun and Cozumel.

Despite its lush mountain setting, Omealca's poverty is striking. One-room concrete houses line crooked, dirt streets where dogs roam unattended. Garbage is strewn on the roadsides. Residents say there's little work outside the sugar cane fields, and most of the men have ditched the town for the United States to find jobs.

Others turn to drug trafficking, evidenced by the federal police who now patrol the town square with assault rifles.

Adrianna arrived in Omealca in the summer of 2004. At first, it looked as if she'd finally found some stability.

She loved playing with her cousins. And she began government-funded preschool in a one-story complex with an outdoor play area a few blocks from her home.

But within months, teachers saw Adrianna come to school without proper clothes for the weather. She was often cold and hungry. School director Albina Cruz Gutierrez spoke with Romero Marin, and the girl's care improved temporarily.

Boy at center of 2007 adoption dispute thrives

Gabriel Brandt, the little boy at the center of a 2007 adoption dispute that captured international attention, is now learning to count to 10 and living a quieter life near the Oregon coast.

Child welfare officials set off an emotional tug of war when they decided to send the toddler, a U.S. citizen, to Mexico to be raised by his grandmother.

Angela and Steve Brandt of Toledo, who had been Gabriel's foster parents since he was 4 months old, were devastated by the decision and worried about the boy's safety. They sued to keep him.

The Brandts prevailed, but not before drawing Gov. Ted Kulongoski, then-U.S. Sen. Gordon Smith and others into debate over sending children from Oregon foster care to other countries to be adopted by relatives.

Two state adoption panels recommended sending Gabriel to live with his paternal grandmother, Cecilia Martinez, in San Jose Miahuatlan, a small farming community outside Mexico City.

Mediated talks between the Brandts and Martinez led to an agreement that allowed the Brandts to adopt Gabriel but ensures contact with family in Mexico.

Last May, the Brandts took Gabriel to Mexico. Angela Brandt said Gabriel's grandmother and family were gracious hosts but that conditions of the home and village were "so much worse" than she expected.

The families talk occasionally by phone, but there are no plans for another visit to Mexico, Angela Brandt said. "We're not wealthy."

Born Gabriel Allred, but now named Gabriel Justice Brandt, the boy enjoys singing the "ABC song" and is quite possibly "the most finicky eater on the planet," his mother says.

He lives with four older brothers and two dogs. He adores "Teaspoon," a puppy the family got last Christmas, and "Bonnie," a golden retriever who "tolerates him rolling around with her," Angela Brandt said. "He told me he wants '1, 2, 3, 4, 5 dogs!'"

— Michelle Cole

In December, five months after Adrianna's arrival, her grandfather, Joel Romero Palacios, went to Desarrollo Integral de la Familia, the Mexican child welfare agency, and told them Adrianna was the victim of family violence.

Information about that report made it back to Oregon authorities via the Mexican Consulate, including an assessment by a welfare agency psychologist that said Adrianna had "defecated in her underwear," so Romero Marin "bathed her outside with cold water."

Perillo said he made phone calls to Mexico, talking with the psychologist, the social worker and Romero Marin. His notes do not describe what they talked about even though department guidelines require detailed documentation.

Perillo never talked to Adrianna's teachers, saying he assumed they would report any problems to the Mexican social workers.

He had to trust his counterparts in Mexico who told him Adrianna was all right, Perillo said. "What could I do? I had no choice."

Still, Perillo admitted that he wasn't getting the regular written updates on Adrianna that he'd requested. After the December report, he received no other written report until April. His monitoring largely meant monthly phone calls to Romero Marin.

Perillo also occasionally spoke with Adrianna.

On May 16, 2005, he wrote in the case file: "I talked to Adriana (sic) who seems fine. I told her I was going to Mexico next week. Adriana (sic) asked me if I was going to visit her. I told her I was going to another place in Mexico. She said, 'OK.'"

It would be the last contact he'd have with the girl.

Cries for help

Mexican welfare workers' spotty communiques about Adrianna's new life in Mexico made no mention of what Adrianna's family members, teachers and even some neighbors knew: The 4-year-old American girl was being beaten regularly.

By May, the principal and several teachers at Adrianna's school began a desperate effort to get the Mexican child welfare agency to pay attention. They took daily pictures of Adrianna's bruises and wounds and went to the agency's offices pleading for help.

None of the teachers' information was ever conveyed to Oregon officials, who still had responsibility for Adrianna.

On May 19, Albina Cruz Gutierrez, the school's principal, wrote a letter to the head of the welfare office in Omealca asking for urgent help because Adrianna was showing up at school with bruises on her face, hands, legs and back.

Officials responded with a letter that said a social worker visited the school May 23, assessed all the children and found them to be in "perfect health." Adrianna, the letter noted, was absent from preschool that day.

Cruz Gutierrez then went to the local office and urged them to investigate. "They said, 'Don't worry,'" she recalled. "'We'll investigate.'"

But no investigation began.

Frustrated, the principal dispatched two teachers to Xalapa, the state's capital, to see whether child welfare officials there might help.

"We told them that, if they didn't do their jobs, we were going to the prosecutors and going to press charges," Cruz Gutierrez said.

The principal also sent two teachers to Adrianna's home to check on her after she'd missed several days of school. The teachers did not see her, so Cruz Gutierrez went to speak with Romero Marin.

"She told me Adrianna didn't behave," the principal recalled. "I told her I didn't want her to hurt Adrianna and she should treat her like her other children."

Adrianna returned to school. But each day, teachers say, they found new cuts, bruises and burns, which they fastidiously documented in photos and written reports.

On June 6, the school's records show Adrianna came to preschool with a large bruise on her face, near her mouth. She told teachers she'd bitten her lip.

Two days later, Cruz Gutierrez and teachers checked Adrianna again and found a new bruise on her stomach. Adrianna said it was a mosquito bite.

Music teacher Jazmin Juarez Benitez spent much of her time off looking for help for Adrianna.

After fruitless visits to the child welfare offices around the state, she went to a Mexican human rights group, where she was told she needed to go through child welfare authorities. Frustrated, and convinced that the little girl was in danger, Juarez Benitez also went to the state attorney general's office in Cordoba, a bustling city a half-hour's drive from Omealca.

Prosecutors told her to gather all the evidence of abuse and get Adrianna's birth certificate and other paperwork in order.

When she reported back to Cruz Gutierrez, the principal called the preschool staff together to discuss how to proceed.

"I wanted to see if we had enough evidence," she recalled. "We did not have enough. We were gathering it."

Some of the teachers discussed kidnapping Adrianna for her own safety. Some were fearful.

"Omealca is known as a very violent and aggressive place," Juarez Benitez said. They were supposed to work through the welfare agency, but the officials charged with caring for the child repeatedly ignored their pleas.

Juarez Benitez said she was tormented.

"I felt Adrianna needed help urgently," she said in a phone interview a few weeks ago. "I felt very handcuffed."

On June 10, a Friday, teacher Caizero Aguilar questioned Adrianna about her abuse. She got no answers.

Frustrated by the apathy of welfare officials and the child's obvious pain, the teacher reached for her faith. The angels, she promised Adrianna, would protect her.

On Monday, Adrianna didn't show up for preschool. Hector de Jesus Luna, Romero Marin's husband, told the principal, Cruz Gutierrez, that the girl was sick and he was taking her to the doctor.

Two hours later, the principal called the doctor to check on Adrianna.

The little American girl was dead.

Susan Goldsmith: 503-294-5131; susangoldsmith@news.oregonian.com

Michelle Cole: 503-294-5143; michellecole@news.oregonian.com

Adrianna's Story - oregonlive.com